Sound Basics

As mentioned in the introduction, I know very little about how sound works. I've always heard the term "sound wave" thrown around, but I didn't really understand what meant. Here's my understanding after reading a few articles about sound.

The ultimate goal in producing sound is to cause ear drums to move, which is what produces the signals that we interpret as sound. They move when the outside air pressure changes, and thus can be made to vibrate when the air pressure increases and decreases. When there is a high vibration frequency, we interpret this as a higher pitched sound, and at a low frequency, we hear a low-pitched sound. The magnitude of the pressure differentials is what we call "volume."

Here's a more in-depth video explanation.

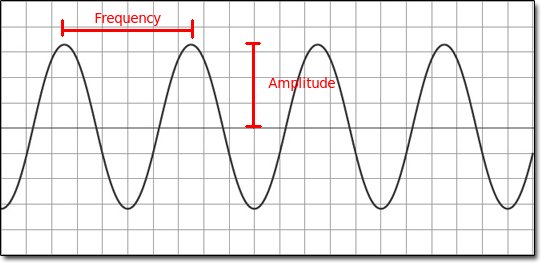

So how does this all tie to the common visualization of sound, the "sound wave" that we're all familiar with? The graph for a sound wave is an oscillating line, where the x axis represents time, and the y axis represents the level of air pressure. The high and low y-axis values of waves are respectively known as the crests and troughs. The vertical height between a crest or trough and the middle of the y-axis is called the amplitude of the wave; this is the volume of the sound. The horizontal distance between two crests or two troughs is the wavelength. Generally speaking, the wavelength controls how many oscillations over time are in the wave, which is known as frequency. Frequency sets the pitch of the sound.

The most common way to create sound electronically is through speakers. My simplified understanding of a speaker is that it consists of an electromagnetic coil, a magnet, and a flexible cone. the electromagnet receives electrical currents that cause it to reverse polarity. The magnet is mounted such where it moves up or down while it responds to the electromagnet's changes in polarity. The cone is attached to this magnet, so as the magnet moves, the cone extends and compresses. This causes the changes in air pressure that produce the sound.

How a computer's sound card sends the electrical signals to drive this electromagnet is beyond what I've looked into so far. The audio device driver for your sound card of course takes care of the interface between an audio-playing application and whatever communication bus is used to reach the sound card, but that's also more than I want to get into. However, I do want to mention how the application tells the audio device driver to play sound.

At least for the device drivers that I've seen, the main way to output audio is to send it audio samples, preceded by metadata about the incoming samples. What do I mean by samples?

Take a look at the sound wave above. How many "y" values are there? That may seem like a strange question; there is a y value for every x value. And how many x values are there? This is something you can't count; there are infinite points. Between any two numbers, no matter how close together they are, there lies another number.

Sound, as with any wave, is what you'd call an analog or continuous signal, meaning the values of the signal are not countable. Digital computers are only able to deal with discrete, quantized (countable) signals; in fact, the meaning of the word "digital" ultimately comes from the act of counting on your fingers. So how do we produce an analog signal from digital data?

This is where sampling comes in, and this applies to more than just sound. At periodic points, while we consume or simulate an analog signal, we record a single measurement representing a range of time. The amount of time between these samples is called the sampling rate. The higher the sampling rate, the more points of data we have for each unit of time, and thus higher sample rates mean more accuracy in representing the analog signal. However, no matter how high the sampling rate is, it can never exactly represent an analog signal. But at some point it's going to be so close that our ears cannot tell the difference.

Just as there are infinite number of time points on the x-axis, which we make countable through sampling, there are an infinite number of points on the y-axis. We have to make these possible signal amounts countable as well. I won't go through the whole explanation of what binary numbers and bits are, but suffice it to say that the number of possible values for a given number of bits is 2n. Each analog value is "rounded" to fit into one of these discrete slots.

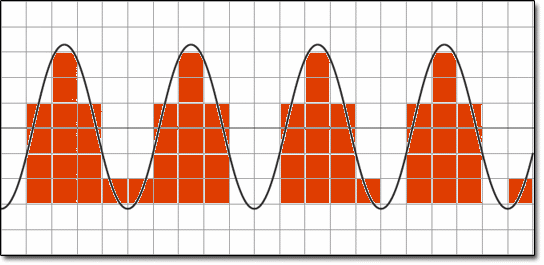

If you're a visual person, sample rate and bit depth are the equivalents of digital image pixelation. Here's what the wave from before looks like with a really low sample rate and bit depth:

Another number that is often talked about is bit-rate. This is simply sampling rate * bit depth. If you are producing 1000 samples per second, with 16 bits per sample, the bit rate is 16,000 bits per second.

Channels are also a key component of digital sound. As you probably know, when people talk about mono, stereo, and surround sound, they're generally referring to the number of speakers. Each speaker produces its own sound wave, so if you're going to output waves from each speaker that are different from each other, you must output two channels of data. The samples for each channel are multiplexed, or alternated, to form one stream of samples. With digital audio, however, you don't actually know how many speakers are present. It's up to the sound card to mix together multiple channels into one signal if there are less speakers than channels.

OK, that's a lot of information in a short period of time. My next article will cover programmatically creating audio samples.